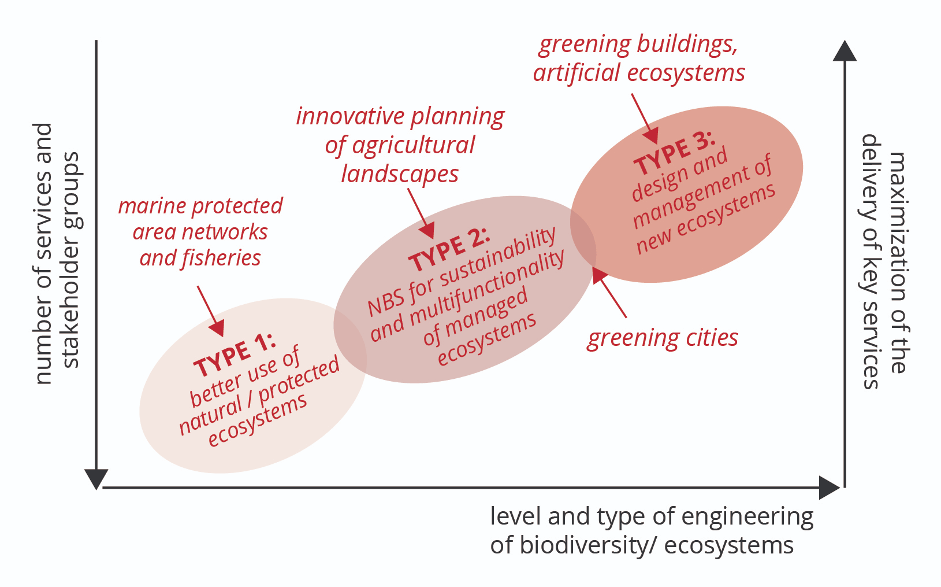

The term “nature-based solutions” (NBS) is very recent, emerging in the 2010s, and is continually evolving as it includes conserving, restoring, or better managing ecosystems. In 2014-2015, the European network BiodivERsA35 mobilized numerous scientists, research funders, and stakeholders, proposing a typology that characterizes NBS along two gradients:

- The extent to which biodiversity and ecosystem engineering are involved in NBS, and

- The number of ecosystem services and stakeholder groups targeted by a given NBS.

This typology highlights that NBS can involve very different actions on ecosystems (from protection to management or even the creation of new ecosystems) and is based on the assumption that the greater the number of services and stakeholder groups involved, the lower the capacity to maximize the supply of each service and simultaneously satisfy the specific desires of each group. Thus, three types of NBS are distinguished:

After implementing NBS, the resulting healthy, resilient, and diverse ecosystems (natural, managed, or created) should benefit human societies (physically and mentally) and biodiversity. While ecosystem services are often valued in terms of benefits to human well-being and the economy of existing ecosystems, NBS explore what changes can be made in those ecosystems (planting or reforesting forests, building wetlands, promoting seagrass meadows, etc.) to:

- Provide a greater amount of services (e.g., more water or greater carbon dioxide fixation),

- Or the same amount at a lower cost (a study in Philadelphia found that meeting a series of urban needs through green infrastructure would cost only $1.2 billion, whereas doing so with traditional infrastructure would raise the figure to $6 billion),

- Or greater protection against disasters (e.g., floods).

NBS goes beyond traditional conservation and biodiversity management principles by introducing people and specifically integrating social factors such as human well-being, poverty reduction, socioeconomic development, and governance principles.

In 2018, the Spanish Government, through the Spanish Commission for the Environment (CONAMA), created a working group for NBS and linked it to the need to promote the application of NBS to make Spanish cities more sustainable. The real estate bubble of the 1980s and 1990s led to the city being conceived as an oasis of brick and concrete—an ecosystem where trees, rivers, and wildlife became decorative elements, whose beneficial effects on inhabitants were forgotten or unknown. This urban model continued to grow, increasing in size and consumption. According to the United Nations, urban environments account for between 60% and 80% of energy consumption and 75% of global carbon emissions. These figures have raised alarms, prompting a renewed discussion on restoring lost nature to cities to make them more sustainable.

In Spain, 80% of the population lives in large cities, while the remaining 20% lives in 80% of the territory. In this regard, a digital observatory called the Nature-Based Solutions Observatory has been launched. This project aims to create a space for knowledge exchange among professionals and entities that support nature-based solutions to address our cities’ environmental, social, and economic challenges. It gathers major projects, documents, and relevant tools on the subject. For example, the Urban Green Infrastructure NBS project in Barcelona is expanding green spaces through initiatives like the “Barcelona Nature Plan 2030,” which aims to add 160 new green areas to enhance urban biodiversity and provide climate regulation benefits.

However, the real solution would be to promote a governance change that directs socioeconomic policies toward reversing the rural exodus to big cities. Today, this remains a utopia despite rural areas offering nowadays all the modern comforts of city life. Governments (national, regional, and local) may only offer the necessary incentives once entertainment options (streaming platforms, social networks, online shopping, etc.) and remote work become further consolidated. Given the current status quo, this remains a utopia, where large cities receive most investments in education, infrastructure, healthcare, etc. Thus, NBS should not be primarily applied to large cities; instead, efforts should be made to adapt population settlements in the so-called “Empty Spain”—empty of people, but where NBS naturally occur, ensuring the quality of life in major cities by providing water, energy, oxygen, food, etc.

Without intending to be pessimistic, examples of NBS outside major cities are emerging in different regions of Spain. One example is the “Life Nieblas” project in the Canary Islands, which utilizes innovative methods such as fog water collection to support reforestation in arid and fire-affected areas. This technique captures water from fog using specialized mesh structures, providing necessary irrigation for young trees without energy consumption.

If NBS focused on these strategies, perhaps in the future, projects would not be needed to mitigate the devastating consequences of severe floods in regions like Valencia, a city that would be awarded the title of “European green capital” in 2025. Spain is seeking to reallocate over a billion euros from EU recovery funds to bolster climate resilience, including developing nature-based flood defenses.

Although some examples measure the greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction of NBS—such as Barcelona’s sustainable architecture project, “the Media-TIC building,” which achieved a 60% reduction in CO₂ emissions through innovative design and renewable energy integration—the overall impact of NBS on Spain’s emissions and carbon sequestration metrics remains largely undocumented. Ongoing data collection and impact assessments are necessary to optimize these solutions and achieve better-informed climate goals.

While NBS play a vital role in Spain’s climate strategy by enhancing carbon sequestration and resilience, their impact on emissions is most effective when integrated with renewable energy expansion and efficiency improvements. Moreover, they should be better applied outside big cities, always considering the local ecosystem and biodiversity improvements from the very beginning.

This Post was submitted by Climate Scorecard Spain Country Manager Juanjo Santos.