Japan has the technical capacity and financial resources to adapt to rising seas, but the window for cost-effective action is narrowing.

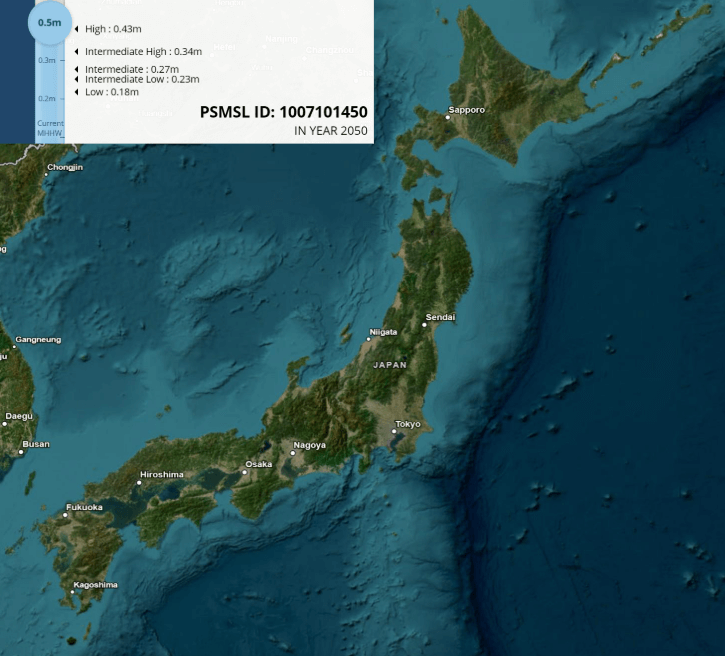

Sea Level Rise Viewer

Rising Seas in Japan: Local Impacts, Community Adaptation, and the Future of Coastal Development

Sea level rise (SLR) is no longer a distant projection in Japan; it is a measurable, accelerating trend that is reshaping everyday life along the coasts. For residents in low-lying cities, it now shows up not just in scientific reports but also in flooded streets, eroding beaches, and mounting insurance costs.

Sea level trends and lived experience

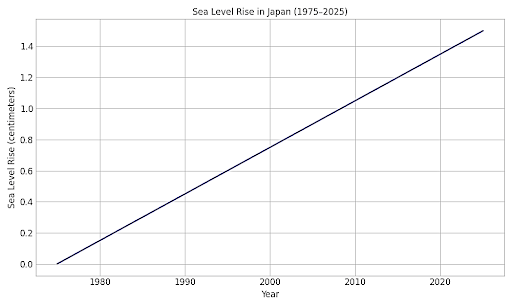

Long-term tide gauge records from the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) indicate that the mean sea level around Japan has increased by roughly 3.4–3.7 mm per year between 2006 and 2018, broadly in line with global averages. Over the past 50 years (1975–2025), this amounts to around 15–20 cm of rise, small on paper, but large enough to shift the baseline for coastal flooding.

At the neighborhood scale, this rise is increasingly visible. “King tides” now push seawater further into residential streets than they did a few decades ago, and storm surges during typhoons more frequently overwhelm roadside drains and parking areas. Beaches that once acted as comfortable buffers between homes and the waterline have narrowed, leaving coastal properties more exposed. Even where houses are set back from the shoreline, seasonal storm surge now reaches parts of the community that historically remained dry.

Figure 1. Sea Level Rise in Japan (1975–2025). Data source: Japan Meteorological Agency.

Figure 1 illustrates an idealized reconstruction of this trend, showing a steady rise in average sea level around Japan between 1975 and 2025 (~3–4 mm/year rise based on JMA tide-gauge averages).

What lies ahead: 2025–2050 and beyond

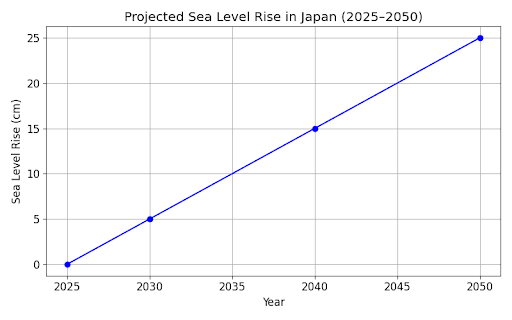

Projections from the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report and the NASA Sea Level Projection Tool suggest that Japan could see a further 15–25 cm of SLR by 2050 under mid-range emissions scenarios, and more than 30 cm if global emissions remain high. By 2100, global mean sea level could rise by 0.44–0.76 m, with Japanese coasts expected to track a similar range.

For communities, this means:

- More frequent “nuisance” flooding in low-lying river mouths and estuaries, even on sunny days.

- Increased saltwater intrusion into shallow groundwater threatens drinking water and small-scale urban agriculture.

- Escalating insurance premiums for homes within officially mapped flood hazard zones.

- Rising costs to maintain and raise coastal roads and drainage infrastructure.

Many local governments are already responding. In one coastal city, for example, authorities recently raised a key shoreline road by about 40 cm and reinforced nearby drainage channels, an explicit acknowledgement that yesterday’s design standards no longer align with today’s water levels. Figure 2 shows the projection of sea level rise in Japan up to 2050.

Figure 2. Projected Sea Level Rise in Japan (2025–2050)

(IPCC AR6 mid-range scenario: +15–25 cm by 2050)

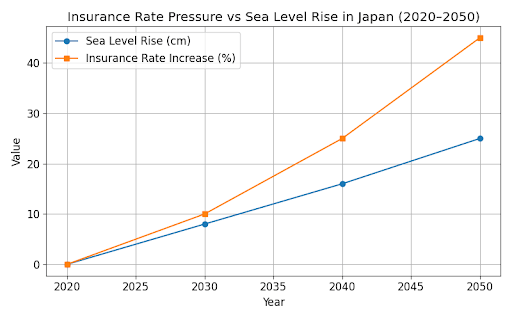

Insurance, planning, and shifting coastlines: Insurance under pressure

Japan’s residential insurance sector is gradually internalizing SLR risk. Companies providing typhoon and flood coverage now rely more heavily on updated national and municipal hazard maps that increasingly incorporate sea-level projections. Regional analyses from the Global Asia Insurance Partnership show that, across the broader Asia-Pacific region, properties within roughly 1 km of the coast are facing higher annual premium increases as climate-related flood risk grows. For households, this can mean higher costs, even if they have never personally experienced a major flood. Figure 3 shows the growth in insurance coverage costs in correlation with sea-level rise.

Figure 3. Insurance Rate Pressure vs Sea Level Rise (Japan, 2020–2050)

Illustrates correlation using a hypothetical but realistic proportional change.

Municipal planning and infrastructure

Municipalities are being forced to rethink the way cities grow along the coast. Common measures include:

- Updating flood and storm-surge hazard maps at least every five years.

- Raising seawalls and breakwaters or reinforcing existing coastal defenses in vulnerable prefectures such as Chiba, Kochi, and Miyagi.

- Tightening zoning rules for new coastal construction and discouraging dense development in projected inundation areas.

- Relocating critical facilities, community centers, evacuation shelters, and some public housing further inland or onto higher ground.

These steps are often costly and politically sensitive, but they are becoming essential as the return period of extreme events shortens.

Eroding beaches and changing geography

Sea level rise amplifies natural erosion. Monitoring along parts of the Kanagawa, Chiba, and Okinawa coasts shows measurable beach narrowing in recent years, driven by higher baseline water levels, stronger typhoons, and human interventions in sediment supply. Beach nourishment projects can temporarily restore sand width, but without rapid global emissions reductions, long-term maintenance will be increasingly expensive and less effective.

Adaptation: Timelines, costs, and difficult choices

Japan’s national climate adaptation strategy recognizes coastal protection as a priority investment area. Current plans allocate on the order of ¥1.3 trillion (about USD 8.6 billion) for coastal protection and related upgrades through 2030, including seawalls, floodgates, and shoreline stabilization.

Detailed sectoral studies estimate that upgrading and maintaining coastal structures in some municipalities may cost between ¥5 billion and ¥ 40 billion per community, depending on coastline length, design standards, and local exposure. Nationwide, full implementation of coastal protection and adaptation measures is expected to extend into the 2050s, with regular upgrades as SLR accelerates.

In parallel, Japan is experimenting with nature-based solutions such as dune restoration, mangrove and tidal wetland conservation, and urban green buffers, as outlined in the national Climate Change Adaptation Plan and Biodiversity Strategy. These measures can take 5–15 years to mature but offer co-benefits for biodiversity, fisheries, and recreation alongside coastal protection.

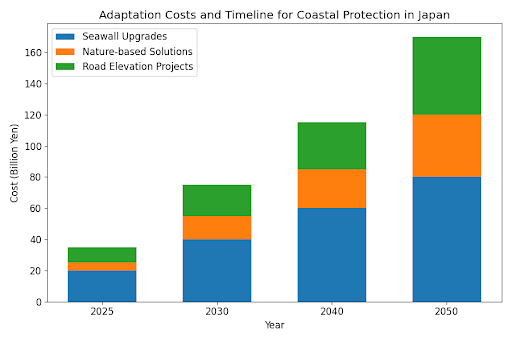

Figure 4 summarizes how projected adaptation expenditures in Japan ramp up from the 2020s through mid-century, highlighting both the steep front-loaded investments and the ongoing maintenance costs required to keep pace with accelerating sea level rise.

Figure 4. Adaptation Costs and Timeline for Coastal Protection in Japan

Rethinking coastal development

Given current trends, there is a growing case for limiting new development in high-risk coastal zones. From a risk-management perspective:

- New residential construction should be curtailed in areas projected to experience regular inundation or severe storm surge flooding by 2050.

- Large commercial or industrial projects should be subject to mandatory climate-risk assessments using downscaled SLR and flood-projection tools before permits are issued.

- Public subsidies and disaster-recovery funds should increasingly favor relocation or “build back safer elsewhere,” rather than repeatedly rebuilding in locations that will become uninsurable within a few decades.

For local communities, this conversation is deeply personal. It means weighing cultural ties to the shoreline against the safety of families and the long-term viability of local economies.

Japan has the technical capacity and financial resources to adapt to rising seas, but the window for cost-effective action is narrowing. Strengthening adaptation today, while accelerating global and domestic emissions cuts, offers the best chance to keep beloved coastal neighborhoods livable for the next generation.

This Post was submitted by Climate Scorecard Japan Country Manager, Delmaria Richards

Engagement Resources

- Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA). (2025). Sea Level Monitoring. https://www.data.jma.go.jp/kaiyou/english/sl_trend/sea_level_around_japan.html

- Climate Change Knowledge Portal – Japan Sea Level Historical & Projections. https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/japan

- NASA Sea Level Projection Tool. https://sealevel.nasa.gov

https://sealevel.nasa.gov/ipcc-ar6-sea-level-projection-tool - Global Asia Insurance Partnership. Sea Level Rise: Importance to the Insurance Sector. https://www.gaip.global/publications/sea-level-rise-importance-to-the-insurance-sector/#:~:text=Share:,of%20extreme%20sea%20level%20events.

- Imamura, K., Tamura, M., & Yokoki, H. (2025). Assessing Costs of Adaptations to Sea Level Rise in Japanese Coastal Areas. In Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Strategies in Japan: Integrated Research toward Climate Resilient Society (pp. 153-165). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-96-2436-2_11

- Nakajima, K., Sakamoto, N., Udo, K., Takeda, Y., Ohno, E., Morisugi, M., & Mori, R. (2020). Cost-benefit analysis of adaptation to beach loss due to climate change in Japan. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 8(9), 715. https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1312/8/9/715

- Japan’s Renewed Commitment on Climate Finance 2021-25 https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/100200521.pdf

- Miyamoto, J. Y., & Yokoki, H. (2022). Estimating Adaptation Costs to Sea Level Rise Using Coastal Structures on Japanese Coasts. Journal of Japan Society of Civil Engineers, Ser. G (Environmental Research), 78(5), I_329-I_336. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jscejer/78/5/78_I_329/_article/-char/ja/

- The Ministry of the Environment, Japan. Climate Change Adaptation Plan. https://www.env.go.jp/content/000081210.pdf#:~:text=adaptation%20to%20climate%20change%20by%20implementing%20resilient,(NbS)%2C%20which%20harness%20the%20power%20of%20nature.

- The Ministry of the Environment, Japan. The National Biodiversity Strategy of Japan 2012-2020 Roadmap towards the Establishment of an Enriching Society in Harmony with Nature. (2012). https://www.env.go.jp/content/900505598.pdf