Japan has made bold promises to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 46% by 2030 (from 2013 levels) and reach net-zero by 2050. While urban areas and younger populations have pushed renewable energy and efficiency measures forward, a substantial group lags, that is, the elderly, low-income residents of rural Japan. Their daily lives, homes, and economic realities present persistent hurdles to climate progress, and must be addressed for national targets to be met.

Key Takeaways from this piece:

• Japan’s climate goals risk exclusion of rural elderly populations.

- Structural and social barriers hinder their participation.

- Two targeted programs, retrofit vouchers and peer-led outreach, offer realistic solutions.

Who Are Japan’s Most Excluded Group?

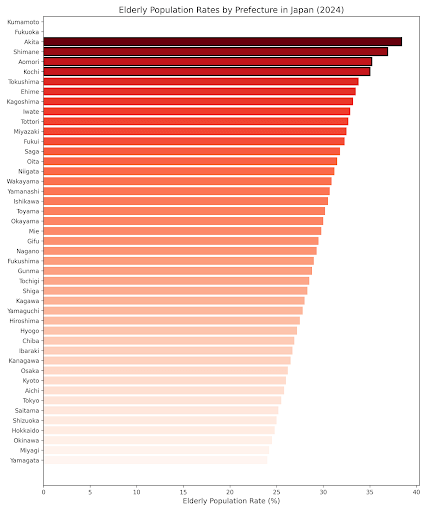

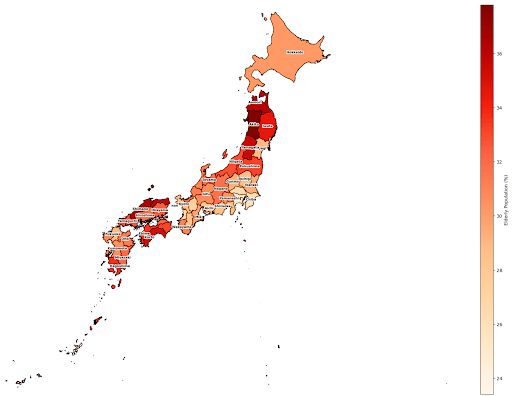

This target group is defined by an intersection of age (65+), low income (most living on modest pensions), and geographic location (rural or depopulating small towns). According to the Japanese government and OECD, about 29% of the total population is 65 or older, with the rate surpassing 35% in rural prefectures such as Akita, Shimane, Aomori, and Kochi. A large percentage of these seniors live alone; projections show that by 2050, up to 26% of older men and 29% of older women will live alone, mostly in rural areas (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Elderly Population Rates by Prefecture in Japan (2024).

Source: Cabinet Office Japan (2024), OECD Environmental Performance Review (2025).

Choose one of these figures above for Figure 1. They represent the same information.

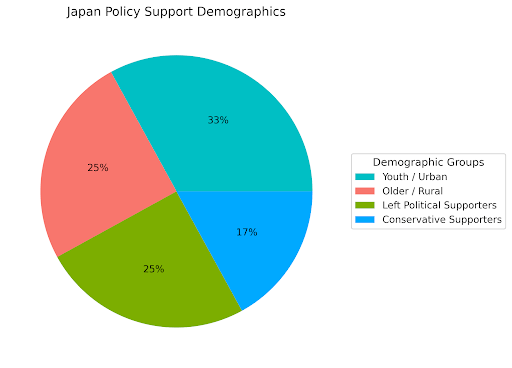

Figure 2. Japan Policy Support Demographics

Source: Cabinet Office, 2024.

The figures highlight areas with the highest proportions of elderly residents and the population’s support for policy (with political alliance), which are typically rural regions characterized by poorly insulated housing, underdeveloped infrastructure, and harsher winters. Elderly residents living in these conditions may have less social support, a greater risk of health-related setbacks, and far fewer opportunities to engage in government programs or climate initiatives.

Why Aren’t They Engaged in Emissions Reduction?

Elderly low-income rural residents remain difficult to engage in climate action for several reasons, including the four main ones highlighted below:

- Energy Poverty: Many individuals live in inefficient homes, use outdated heating systems (such as kerosene stoves), and lack the funds for insulation or renewable energy upgrades. Energy bills consume a higher portion of fixed incomes, and older or inefficient appliances are common.

- Access and Information Gaps: Most national and local subsidy or retrofit programs require digital literacy and online applications; however, many rural elderly individuals are not internet users or are wary of new technologies.

- Cultural and Behavioral Barriers: Familiar routines and strong attachment to traditional ways (such as using familiar stoves or keeping homes warmer in winter) make change daunting. Trust in external advisors may be low, especially when information is not delivered through face-to-face channels.

- Isolation: As rural depopulation accelerates, access to community support, building contractors, and public welfare outreach shrinks. Many seniors have lost regular ties to family, local government, or civic groups.

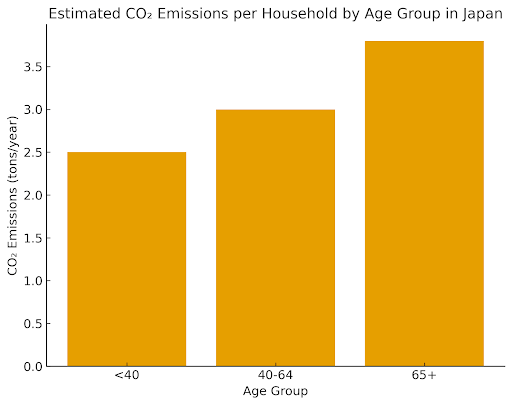

Figure 2. Estimated CO2 Emissions per Household by Age in Japan.

It shows that the elderly households have higher per-household emissions due to less efficient energy use and reliance on heating fuels (adapted from METI, OECD, 2025).

Two Proposed Cost-Effective, Realistic Solutions are:

- Comfort-Smart Retrofit Voucher Program

Proposal: Launch a targeted voucher system for rural seniors, covering up to 100% of the cost for insulation, high-efficiency heaters, and upgraded windows and doors.

Why it Matters: Building retrofits are the single most effective method for improving comfort while slashing heating and cooling emissions in old homes. The voucher removes the up-front cost barrier and is paired with local outreach by trusted actors (municipal leaders and health workers).

Implementation:

- The Ministry of the Environment, working in conjunction with local municipal offices, would identify eligible seniors using residency and welfare records.

- Contractors participate in mobile retrofit teams, travelling to farming areas and small towns.

- A simple paper or phone application process, with in-person help, ensures accessibility.

- Program success would be measured by the number of retrofits completed and changes in energy consumption among participating homes.

- Peer-Led Climate Champions Program

Proposal: Establish a network of trained senior “climate champions” within each rural municipality, who will run community workshops and demonstrate low-carbon living strategies, sharing these approaches with peers and supporting them in practical energy-saving behaviors.

Why it Matters: Seniors trust information from their peers more than from outside experts. Senior-run “open houses,” hands-on help with energy monitors, and group discussions can drive meaningful, persistent changes at low cost. Small grants for local champions fund simple energy reduction tools.

Implementation:

- Local governments and NGOs recruit respected retirees as community leaders and advocates.

- Training (in-person, not digital) in climate basics, energy saving, and communication.

- Monthly gatherings in local community centers to share experiences, distribute tips, and track energy savings.

- Effectiveness would be monitored through participation rates, pre- and post-energy data, and feedback-collected in-person or by mail.

Expected Impact

Together, these programs directly address both structural (inefficient housing) and social (information, trust) barriers. By enabling and empowering rural elderly individuals, Japan can reduce household emissions; improve the quality of life for a vulnerable population, and make climate action feel both relevant and achievable across the country.

Decision-Makers Contact:

- Mr. Kihara Shinichi

Director-General for Energy and Environment Policy at Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI)

Email: https://mm-enquete-cnt.meti.go.jp/form/pub/honsyo03/contact_us - Mr. Shinya Matsumoto

Director, Office of Regional Decarbonization Policy

Ministry of the Environment, Japan

Email: shinya_matsumoto@env.go.jp

This Post was submitted by Climate Scorecard Japan Country Manager, Delmaria Richards.

Learn More Resources

- Cabinet Office Japan, “Annual Report on the Ageing Society Summary FY2024.” https://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/english/annualreport/2024/pdf/2024.pdf

- Huang, L., Montagna, S. et al. “Extension and update of multiscale monthly household carbon footprint in Japan from 2011 to 2022.” Scientific Data, 2023. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-023-02329-2

- Huang, Y., Li, X., & Guo, X. “Unequal Paths to Decarbonization in an Aging Society: A Multiscale Assessment of Japan’s Household Carbon Footprints.” Sustainability, 2025. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125627

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Japan 2025.” https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2025/03/oecd-environmental-performance-reviews-japan-2025_947dc3da/583cab4c-en.pdf

- R. Castaño-Rosa et al., “Prevalence of energy poverty in Japan: A comprehensive analysis,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews (2021). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364032121002963

- S. Okushima, “Double energy vulnerability in Japan,” Energy Policy, 2024. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421524002040