Inequality in Japan: Who Is Left Behind in the Transition to Renewables?

Japan, a nation celebrated for its technological expertise and environmental stewardship, grapples with a paradox. While its urban centers rapidly embrace renewable energy and eco-friendly transportation, significant demographic groups face substantial obstacles in accessing affordable and sustainable services. From the aging populations in rural hamlets to the economically disadvantaged in urban abodes and the often-overlooked migrant worker communities, segments of Japanese society are increasingly excluded from the nation’s green revolution. This exclusion threatens Japan’s ambitious climate objectives and intensifies existing socio-economic disparities.

One of the most critically affected demographics is the elderly residents of rural Japan, particularly those in “Genkai Shūraku” communities. Muramatsu and Akiyama elaborate on how these villages teeter on the edge of sustainability, plagued by aging populations and dwindling numbers. Securing affordable renewable energy is a daunting challenge in prefectures such as Akita, Shimane, and Kochi, where senior citizens constitute over 40% of the populace. Many of these communities still depend on outdated and environmentally taxing systems such as kerosene heaters and diesel generators, and their electrical grids have seen minimal integration of solar or wind technologies.

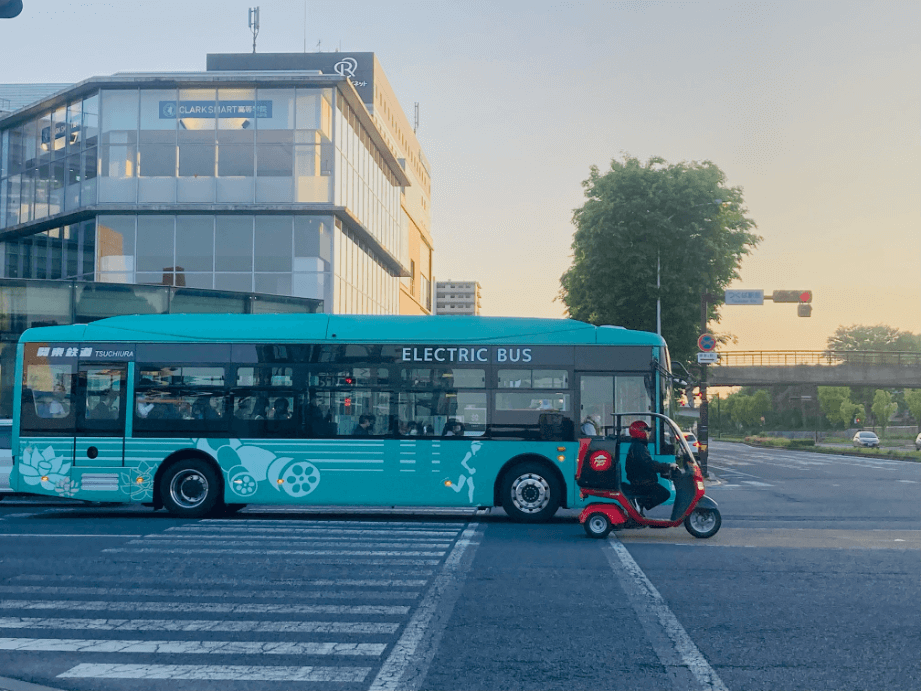

Urban centers also present their own set of challenges. Low-income residents, especially single-parent households and “freeters,” often engage in part-time employment and struggle to afford the initial costs of adopting renewable energy solutions. Residents of older, less energy-efficient apartments on the outskirts of metropolises like Tokyo, Osaka, and Fukuoka often cannot afford to invest in rooftop solar panels or electric vehicles (EVs). Consequently, they rely heavily on traditional grid electricity, which is usually generated from fossil fuels, and have minimal public transportation systems (in terms of available numbers) that are slow to incorporate electric options.

Additionally, migrant workers, particularly those participating in technical training programs from Southeast Asia, represent another marginalized group. Typically housed in employer-provided dormitories, they often lack the autonomy and financial means to adopt clean energy solutions or access sophisticated waste management amenities. Instead, they depend on communal utilities powered by fossil fuels and basic sanitation systems.

These disparate groups share common socio-economic vulnerabilities, including low income, limited educational and technical training opportunities, minimal property ownership, and geographic isolation. Rural communities, deeply rooted in Japan’s traditional values of self-reliance and communal resilience, often find their cultural pride overshadowed by the daily infrastructural decay and resource scarcity. Conversely, urban low-income households and migrant workers represent Japan’s increasingly insecure labor market. This growing class lacks the political influence or financial stability necessary to shape energy and transportation policies.

Several interconnected factors exacerbate this inequality:

- High upfront costs: The significant initial investments required for solar panels, electric vehicles (EVs), and home battery systems pose a substantial barrier. Compounding the negative impacts, government subsidies often fail to reach those who lack property ownership or stable employment.

- Infrastructure deficiencies: Remote areas are hampered by aging and unreliable grids, making the integration of renewable energy both technically challenging and economically unviable.

- Policy gaps: Renewable energy initiatives often prioritize urban centers and commercial sectors, with incentives rarely extending to low-income renters or temporary housing facilities.

- Limited awareness: Information regarding renewable energy programs is often complex and inaccessible, particularly for elderly populations and migrants unfamiliar with the language and applicable digital platforms.

Without access to affordable renewable alternatives, rural seniors depend on kerosene for heating and gasoline-powered vehicles for transportation. Low-income urban residents are often locked into traditional electricity contracts, while migrant communities rely on energy sources provided by their employers and the fossil fuel grid. This reliance drives up living costs and increases their carbon footprint, undermining Japan’s national climate goals, including its quest for carbon neutrality by 2050.

The insecurity in access to energy and transportation significantly diminishes the quality of life for these vulnerable populations. Rural residents face harsh winters with inadequate heating and must travel considerable distances to access essential services, such as healthcare and shopping, often without the option of electric public transportation. Urban households face high utility bills, as well as limited mobility due to the high costs and inaccessibility of electric vehicle (EV) infrastructure. Migrant workers suffer from substandard living conditions and health risks due to the lack of reliable energy and comfortable waste management services.

These inequities exacerbate systemic poverty and social exclusion, making it increasingly difficult for marginalized groups to improve their socioeconomic status.

The Japanese government has acknowledged these disparities and introduced several measures to address them. The Green Growth Strategy, launched in 2020, aims to increase the accessibility of renewable energy by offering expanded subsidies for residential solar panels and low-interest loans for electric vehicle (EV) purchases (Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, 2021). The Rural Revitalization programs also include provisions for modernizing energy infrastructure in depopulated areas by promoting microgrids and community-owned solar projects.

Similarly, non-governmental organizations also play a crucial role; for example, the Japan Community Power Association supports rural communities in establishing citizen-owned renewable energy projects, ensuring that profits remain within the community. Pilot projects in regions such as Hokkaido and Tottori demonstrate the potential success of community solar farms and shared renewable energy schemes, even in areas with declining populations.

It can be argued that more robust regulatory mandates, greater decentralization, and targeted outreach to migrants and renters are necessary to prevent further marginalization of vulnerable groups.

For Japan’s green transition to succeed, it must extend beyond urban centers and the middle class. Ensuring equitable access to renewable energy, sustainable transportation, and effective waste management must be a central component of climate policy. Empowering all citizens to participate in the energy transition is a matter of social justice and essential for achieving genuine sustainability.

For more information, visit the sites listed below.

This Post was submitted by Climate Scorecard Japan Country Manager Delmaria Richards.

Sources

- Agency for Natural Resources and Energy. (2022). Annual Energy Report 2022. Tokyo: Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry.

- Government of Japan. (2021). Green Growth Strategy Through Achieving Carbon Neutrality. Retrieved from https://www.meti.go.jp/english/policy/energy_environment/global_warming/ggs2050/index.html

- Hosogaya, N. (2020). Migrant workers in Japan: Socio-economic conditions and policy. Asian Education and Development Studies, 10(1), 41-51.

- Japan Community Power Association. Retrieved from https://www.communitypower.jp/

- Komine, T. Japanese Regions in the Face of Depopulation and the Trend of Compact City Development. https://www.japanpolicyforum.jp/blog/pt201505070232494814.html

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. Green Growth Strategy: Achieving Carbon Neutrality by 2050. https://www.meti.go.jp/english/policy/energy_environment/global_warming/ggs2050/index.html

- Ministry of the Environment Japan. (2022). Annual Report on the Environment, the Sound Material-Cycle Society and Biodiversity in Japan 2022. Tokyo: Ministry of the Environment.

- Muramatsu, N., & Akiyama, H. (2011). Japan: Super-aging society preparing for the future. The Gerontologist, 51(4), 425-432. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr067

- (n.d). Regional Revitalization in Japan. https://zenbird.media/regional-revitalization-in-japan/